Brother worm and sister wasp

Near the house where I lived as a child, there was a massive oak we called the Firefly Tree. It stood solitary in the middle of a tobacco field, and every summer attracted apocalyptic numbers of fireflies. Even from a distance, the whole tree glowed and pulsed like a disco party.

Decades later, and hundreds of miles away, I keep hoping the fireflies will choose a tree near me as their party site, but it hasn’t happened yet and probably never will. Our firefly populations are dwindling.

Fireflies exist all over the world, on every continent except Antarctica, and thrive especially in tropical regions. Of the over 2,000 different species that exist globally, some are at risk. Several of the over 120 firefly species in the United States have been designated as critically endangered, endangered, or vulnerable. The Common Eastern Firefly—the type most likely to be seen in my area—is not at risk, but we still don’t see as many as we used to.

Some who are concerned about pressures on fireflies and other species have chosen to rewild areas of their property, or forego pesticides. Yet as with any other ecological threat, it’s hard for individual efforts to make much of an inroad against corporate-backed industry.

And now, as the Trump administration eliminates environmental protections and opens public lands for drilling, it will be even harder to protect at-risk species. I’d like to think that the loss of fireflies would change people’s minds, but I’m not naive enough to believe that a movement that has been fine with horrific attacks on immigrant families, including on pregnant women and sick children, will be deterred by threats to a tiny insect, no matter how lovable.

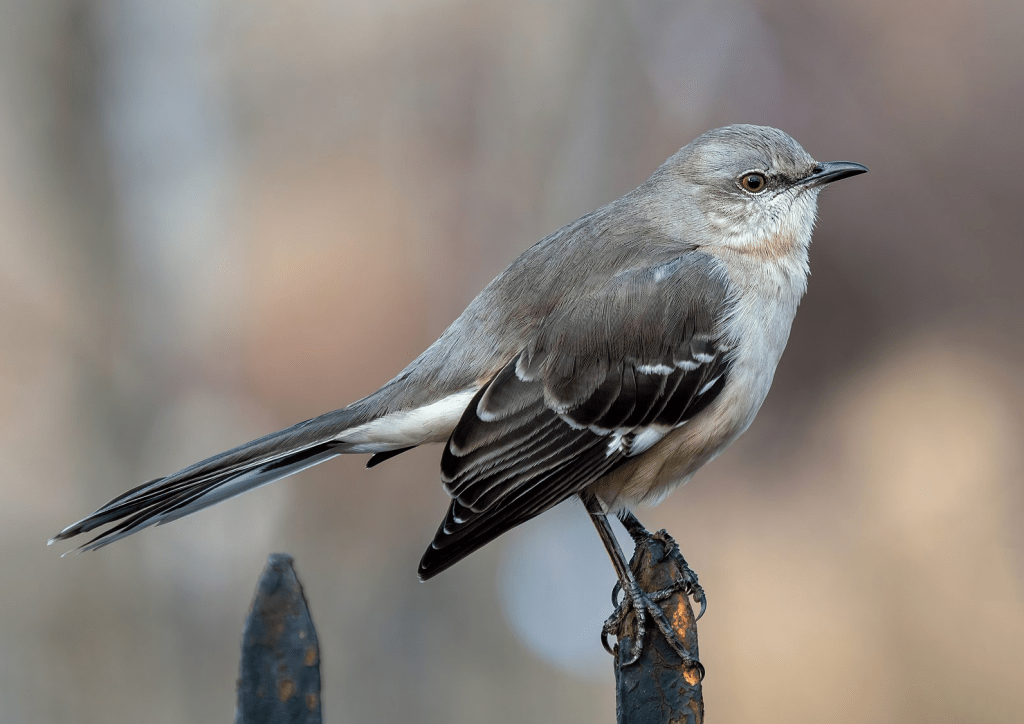

Still, fireflies do seem perfect emissaries for the insect population. They don’t bite or sting, they don’t smell funny, all they do is take to the air and shine. Even people who generally dislike bugs find them enchanting. I’m reminded of Atticus in To Kill a Mockingbird, telling Jem: “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy.” And then he says the line from which the book takes its title: “Shoot all the bluejays you want, if you can hit ’em, but remember it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

When I was about seven, I encountered a kid who thought it amusing to smash the fireflies and rub the guts on his jeans to make them glow. My inclination at that age was to resolve disputes via violence, so I tackled the kid and pummeled him a bit, to teach him a lesson. I guess I figured it was a sin to kill a firefly.

But mockingbirds don’t sing as a favor to humans, and fireflies aren’t putting on light shows for our benefit. They live their own lives, communicating with one another, establishing relationships and connections that have nothing to do with us.

I’ve been pondering this as I consider how many Trump supporters I know claim to be nature lovers. I know organic growers, farmers’ market managers, folks who love hiking and kayaking and exploring our national parks, who continue to support this administration despite its assaults on the environment.

Maybe some of them are convinced, thanks to well-funded propaganda campaigns, that the administration is not doing the things it is doing. But it’s also a fact that our modern western approach to nature is fundamentally exploitative. We value nature for what we can get out of it.

And that makes our affection for the natural world conditional. No matter how much we enjoy hiking in parks or watching fireflies, we’ll easily sacrifice a nature preserve for something that gives us even more pleasure: maybe the wealth derived from leasing to an oil company. Maybe the security of keeping one’s social capital by refusing to rock the boat.

This is an issue in Christian culture, going back to interpretations of the second creation myth in Genesis. God, according to these interpretations, made the world exclusively for humanity’s benefit. This theological idea has offered repeated justifications for the harm human beings have done to other living things.

One reason I appreciate the Christian doctrine of original sin is that it serves as a framework for thinking about our broken relationship with nature, which is a factor even in our supposed love of living things. We want to bathe in forests and get in touch with our inner wildness and recharge.

But maybe, sometimes, the best way we can love the natural world is to leave it alone. Having trampled so many ecosystems, why do we assume we still get to turn to them for solace? It seems like an abusive relationship, in which someone berates and demeans their partner then expects them to offer intimacy.

Our relationships with nonhuman animals really do shape how we treat other humans. Women have noted that you can tell a lot about a man from the way he treats domesticated animals. Does he feel entitled to their affection and get angry when they don’t give it? Does he violate their boundaries? Does he train dogs or horses by means of intimidation? Does he resent cats because of their independence? These are all red flags.

I’d like to propose that Christians spend some time reflecting on Genesis’ other creation myth: In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. In this version, the cosmos is created and unfolds out of chaos, harmonious and sublime, and even though no humans are in it yet, God calls it “good.”

The idea that we should be more respectful of nature’s boundaries is complicated by the fact that we are also part of nature and that, having disrupted it, it’s on us to try to restore balance. Also, not everyone is equally complicit in the harm done to nature, and many are victims of that same violence inflicted on ecosystems. Many of us are closer to the fireflies than we are to the billionaires, something St. Francis realized, maybe, when he spoke of living things as his brothers and sisters. But it’s not just the fireflies we’re connected to. We’re connected to the creatures we find strange and unappealing, too—the ones that fail to delight us or sing for us or put on light shows. We’re connected with the worms and the wasps, also.

It’s good to appreciate the song of the mockingbird or the sight of a tree lit up with fireflies. But this doesn’t mean we should treat nature as something created exclusively for our benefit. And we need to be ready to defend species even when they don’t delight us.

Maybe it’s a sin to kill a bluejay, too.

At messyjesusbusiness.com you can read more by this author and more about our relationship with the natural world.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rebecca Bratten Weiss is a writer and academic residing in rural Ohio. She is the digital editor for U.S. Catholic magazine and can be found at rebeccabrattenweiss.com.

One Comment